Pregnant with meaning and purpose, Aboriginal art uses lines and dots to narrate mythical events and topography of a region.

Who are the Aborigines? They are undoubtedly one of the best known by name, but perhaps the least known and understood peoples in the world. They have an impressive cultural tradition, yet a vast gulf of civilisation separates them from us. Aboriginal culture is one of the last, if not the last, Paleolithic (early Stone Age) culture with documented traces of at least 60,000 years. Contrary to popular belief, Aboriginal Australians have never constituted a single nationality or defined themselves by a single common term. Before British colonisation, which began in 1788, the continent had been inhabited by more than two hundred tribes, which had separate names and spoke different languages.

What is the relevance of Aboriginal art to modern man and to what extent is the white man able to understand it? For Europeans, who have lost their close connection with their cave-painting ancestors of Altamira and Lascaux, contact with this culture provides an opportunity to reflect on their own origins. Not only does the contemporary viewer gain a rare insight into the origins of human expression, but they also have reason to reflect on a rich set of cultural values. In an age of increasing threat from technical civilisation, an understanding of Aboriginal visual language can also help to refine notions of contemporary aesthetics as well as influencing the shape of our future visual representations.

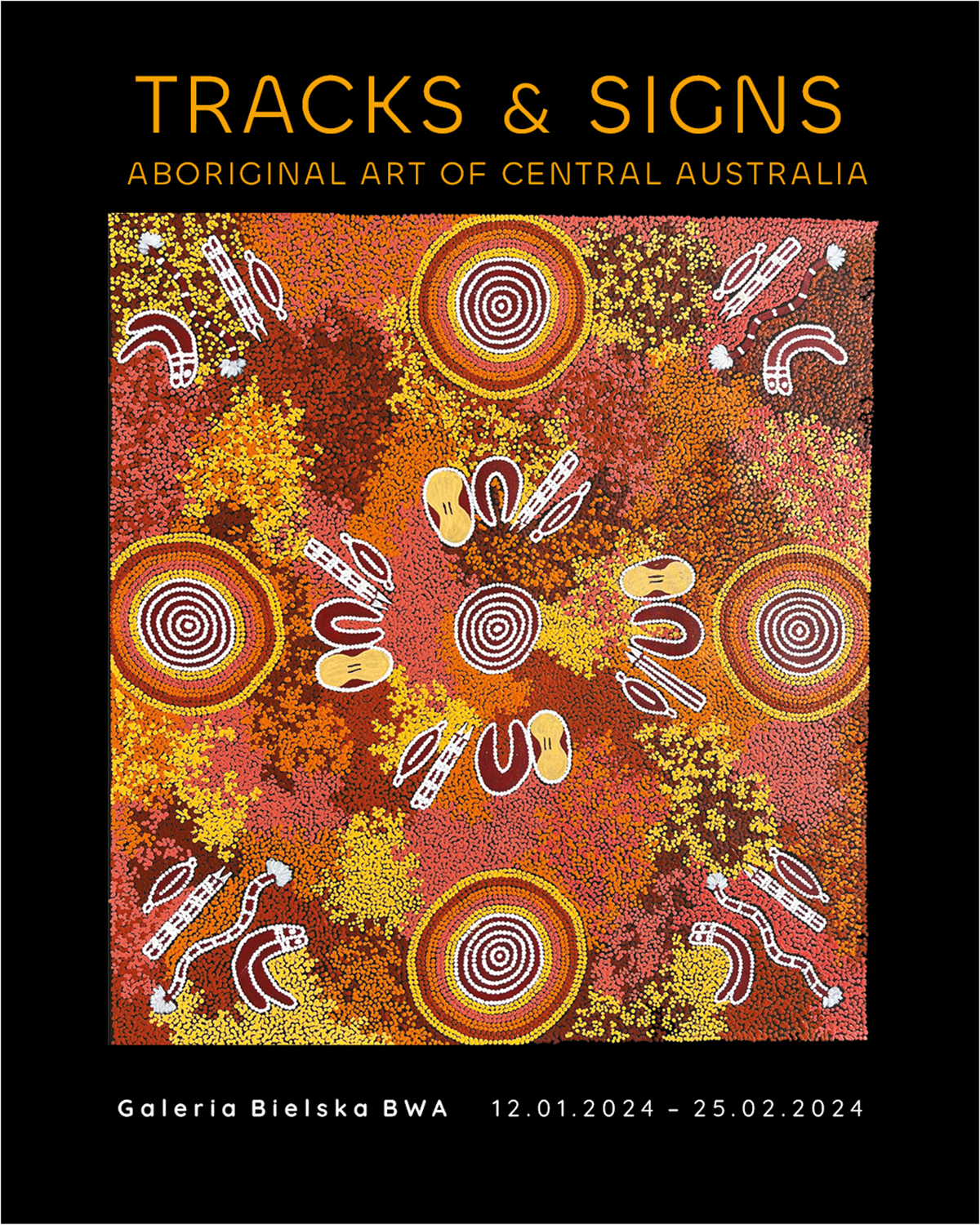

The exhibition at Galeria Bielska BWA will feature 33 paintings from the collection of Julianna and Ryszard Bednarowicz, as well as over a dozen artefacts of Aboriginal art.

The works on display in the exhibition demonstrate the two polarities of Aboriginal creativity evident in the art of Central Australia, east and west of the town of Alice Springs.

The artists from three settlements participating in the exhibition:

UTOPIA – Polly Kngale, Gracie Morton Pwerle, Kathleen Petyarre, Rosemary Petyarre, Helen Rubuntja, Cindi Wallace Nungurrayi;

KIWIRRKURRA – Barbara Reid Napangardi, Thomas Tjapaltjarri, Walala Tjapaltjari, Willy Tjungurrayi;

YUENDUMU – Mary Dixon Nungurrayi, Lynette Granites Nampijinpa, Kathleen Martin Nungurrayi, Bessie Sims Nakamarra, Paddy Sims Japaljarri;

Curators: Ryszard Bednarowicz, Marek Tomalik

Traces and Signs. Aboriginal paintings from Central Australia

Galeria Bielska BWA, Lower Hall

12.01.2024 - 25.02.2024

Opening and a curator tour by Marek Tomalik:

Friday, 12 January 2024 at 6 pm

www.aboriginal-australia.art

________________________________________________________________________________________

Excerpts from an essay on the history, nature and significance of Aboriginal art by Richard Bednarowicz:

The Aboriginal art phenomenon began in the heart of Australia (Central Australia) in the early 1970s. In 1971, art teacher Jeff Bardon arrived in the settlement of Papunya, 250 km west of Alice Springs. He found the Aboriginal tribes there stagnant and degenerate. The children were not interested in drawing and painting, preferring to play tag and break windows. Bardon gave cardboard boxes and paints to the adult men and they began to paint their traditional stories (on durable materials), which had until then been created in quite ephemeral forms, such as mosaics on sand, body paintings, or drawings on the ground. (...)

Bardon soon gave the artists canvases and set up the Papunya Tula cooperative, co-owned by the artists. They were provided with acrylic paints and the promotion of their paintings began (...). The size of the painting surfaces increased and the paintings could be rolled up and transported more easily. The colour scale also expanded, and artists began to fill forms and backgrounds with dots, making the works more varied and aesthetically interesting. Hence, this art, sometimes referred to as dot painting, over time ceased to be represented exclusively in ethnographic museums and was

For thousands of years, Aboriginal art has been closely linked to religion and many of the paintings now created for Western buyers continue to depict sacred stories with references to traditional beliefs and events. The pattern-painting in this context serves a much broader function than formal and decorative modernist works. For the artist, it is a testimony and proof of ownership of a specific area, it is a map where there is no scale (...). The painting conveys knowledge and secrets, the content of which is woven into the mythology and broad symbolism of everyday life. The knowledge, beliefs and art in this cultural system function inseparably and are manifestations of sacred creative acts and places where Aboriginal people believe the energy left by the mythical Ancestors emanates.

The form and content of contemporary Central Australian art derives from drawings and mosaics on sand and body paintings. Sand drawings, in the semi-arid area of Central Australia, were the most popular means of visual communication and were used to communicate and educate children on a par with speech. Signs on the sand were drawn with fingers or with a boomerang, and their set was limited to a few repetitive forms such as circles, straight or winding lines, animal signs and finally dots. The graphic signs were combined into so-called “images”: in other words, they were spatially distributed on the surface of the sand rather than in linear order, and the stories they described were intended for all members of the clan.

Aboriginal aesthetics are subordinated to the principle of exact replication of the pattern and the artist paints what he knows about the terrain or object, not what he sees or has seen. The accuracy of the pattern was controlled by other clan members. The paintings were painted on the ground and spatial orientation in this case was not important; categories such as top and bottom, right and left sides, vertical or horizontal composition – had no meaning. (...) The Aboriginal artist painted a map of the land enriched with the essential knowledge necessary for survival, and this map often included landscape elements found on the ground, underground and in the sky.

The artist’s “palette” consisted of four basic colours found in the environment: red, yellow, black and white. These paints were rarely mixed together or layered one on top of the other. In this way, the painted object retained a link to the source of the materials with which it was depicted and combined them with each other.

Aboriginal paintings, seemingly abstract in our perception, are nevertheless full of narrative, much like the paintings of Jan Matejko. The art is filled with meanings and intentions (traces-signs), where each line, circle or even a few dots tells the story of mythical events and depicts the topography of the region.

It should be added that traditional Aboriginal aesthetics, like any other prehistoric art, was not shaped by representational and non-mimetic elements familiar from European tradition, such as the frame, rectangular shape, picture plane or signature. For there are no angles, rectangles, or flat surfaces in nature. The most characteristic feature of this art is its irregular surface and the lack of a defined boundary (frame); thus, a painting was not conceived as a physical limitation imposed on the ability to see. Signature, as a sign of “authentication”, was also alien to the Aboriginal artist; the right to paint specific stories and patterns was culturally sanctioned.

________________________________________________________________________________________ Julianna and Ryszard Bednarowicz– owners of the Mala Art gallery collection, from which the paintings presented in the exhibition are on loan. They have met personally and remain in contact with all the living artists whose works are presented in the exhibition. What's more, they have been given tribal names, Napurrula and Japanangka, by the Warlpiri tribe.

Julianna and Ryszard Bednarowicz– owners of the Mala Art gallery collection, from which the paintings presented in the exhibition are on loan. They have met personally and remain in contact with all the living artists whose works are presented in the exhibition. What's more, they have been given tribal names, Napurrula and Japanangka, by the Warlpiri tribe.

Ryszard Bednarowicz studied Cultural Studies at the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań. In 1982 he settled in Australia, where he obtained a B. A. degree in Art History from the University of Queensland and an M. A. degree in Art History from the University of Melbourne.

He currently lives in Alice Springs. He is the author of “Aboriginal Art”, a book that provides an understanding of the work of Indigenous Australians, as well as catalogues and articles on their art.

Organiser and curator of exhibitions of Polish posters and graphics in Australia. Curator of Aboriginal art exhibitions in Poznań, Warsaw and Szczecin. He is involved in the promotion of Aboriginal art and culture both in Poland and Australia. He is an unquestionable authority in this field.

Julianna Bednarowicz graduated from the Secondary Art School in Koło and completed higher education in pedagogy and art, with a degree in fine arts education, specialisation in teaching with a master's degree at the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń.

Organiser of open-air workshops and curator of exhibitions in Europe, e.g. Germany, Hungary. Since 2004, she has been living in Alice Springs, where, together with her husband, she is engaged in the culture and art of Australian Aborigines.

She has exhibited her work throughout Australia, including in Melbourne in 2015 at the Pol Art Festival, where she exhibited a series of portraits created in collaboration with the Aboriginal artists depicted in the paintings, who painted their stories into a designated part of the painting.

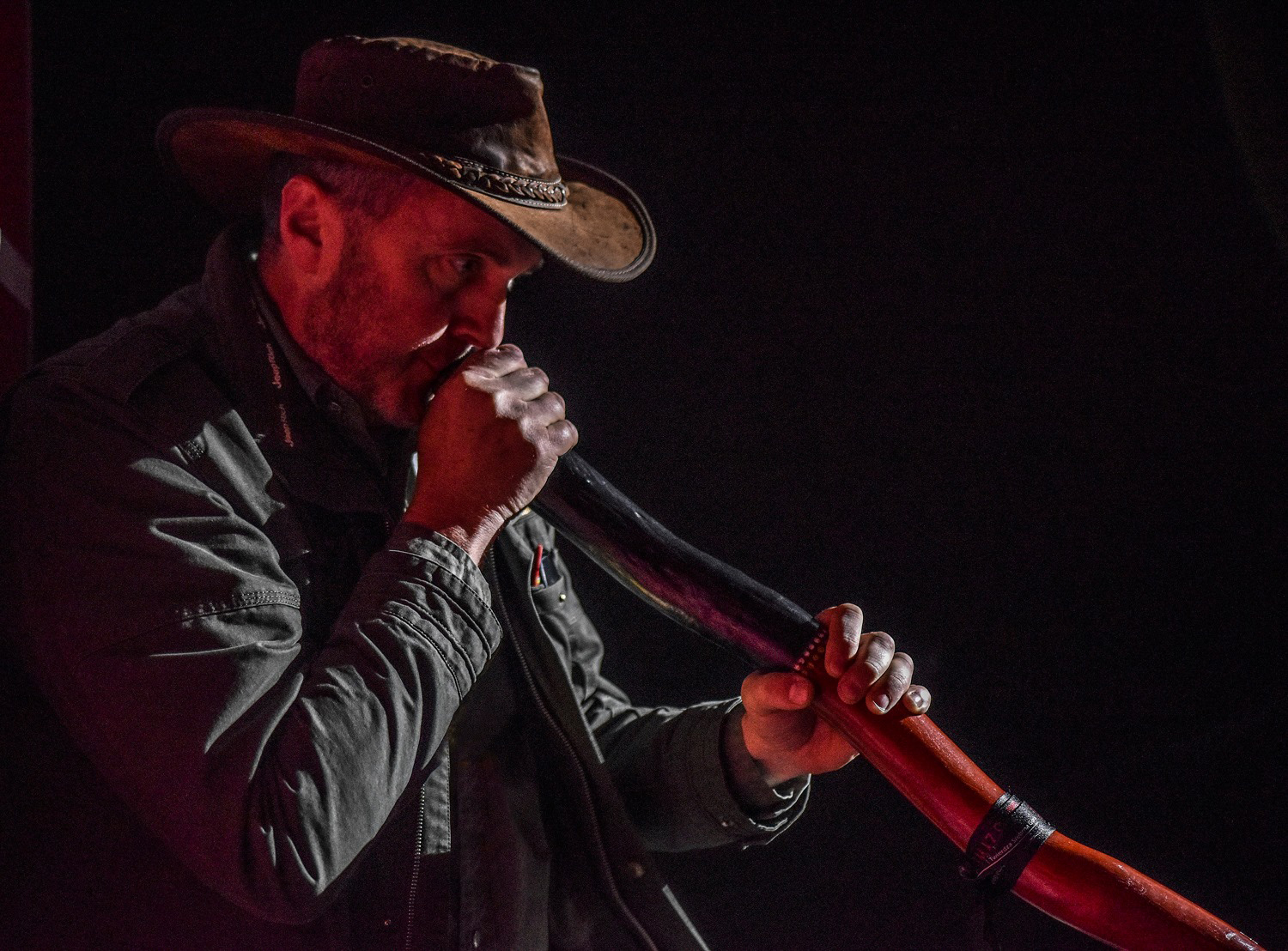

Marek Tomalik – traveller fascinated by Aboriginal art, press and radio journalist, graduate of the Jagiellonian University, resident of Bielsko-Biała. A passionate traveller and expert on Australia, where he has been travelling regularly since 1989. He has organised 16 expeditions to the Australian Outback, 23 editions of the Travellers’ Festival “Three Elements” and many other artistic events. Contributor to National Geographic and Jazz Forum. Author of books and feature reports on travels. Two-time winner of the Kolosy award. For the last six years he has been the host of the Bright Side of the World programme on RMF Classic.

Marek Tomalik – traveller fascinated by Aboriginal art, press and radio journalist, graduate of the Jagiellonian University, resident of Bielsko-Biała. A passionate traveller and expert on Australia, where he has been travelling regularly since 1989. He has organised 16 expeditions to the Australian Outback, 23 editions of the Travellers’ Festival “Three Elements” and many other artistic events. Contributor to National Geographic and Jazz Forum. Author of books and feature reports on travels. Two-time winner of the Kolosy award. For the last six years he has been the host of the Bright Side of the World programme on RMF Classic.

Australia is his place on earth, but he always returns to his nativy Beskidy mountains. He is the author of four books about the fifth continent: “Australia, my love”, “Lady Australia”, “Australia, where flowers are born of fire” and the latter published in 2021 “9 FIRES”.

More at : www.australia-przygoda.com and www.wsednosprawy.pl

Read also about Marek Tomalik’s photographic exhibition “Australia - where flowers are born of fire”, which will be presented at the Aquarium Cafe Club, parallel to the exhibition “Traces and signs - Aboriginal paintings from Central Australia” >>

Free online catalogue of the exhibition

To read the catalogue click on the cover below